Updated on 2021-09-11 by Adam Hardy

Photo by Jack Bassingthwaighte on Unsplash

The unprecedented Australian bushfires in 2020 followed the lost 2019 ‘Unloseable Climate Election’

As we enter the new decade, Australia finds itself flooding the international headlines for all the wrong reasons. The record-breaking bushfires that began in December raged for weeks and were only fully extinguished thanks to unprecedented rainfall. It has shocked people all around the world.

Over January, Australia was hit by the most severe bushfires on record, with a prolonged drought and temperatures never previously recorded in Australia. The record for the hottest day was broken on Wednesday 18th December, with average temperatures reaching 41.9°C.

This extreme weather was driven by complex natural processes. The research shows with the average warming in Australia already at +1oC, the coupling of extreme weather events and anthropogenic global warming is beyond question, except by some whose agenda is clearly non-scientific. Sadly for prospects of real action, such voices can still be heard.

The consequence of this climate change via the tinder dry vegetation has been bushfires at a scale and intensity never before experienced in Australia. The impacts are visceral and severe, with 33 people dead and over 1 billion animals wiped out.

These bushfires consumed a total of 11 million hectares of land, just under the land area of England, much of which was pristine biodiverse bush, as well as rainforest and dried out swamps which don’t usually burn.

It seems Australia has rather dramatically become the canary in the coal mine. The country is at the front line of fossil fuel emission-driven global warming, bearing the full impact of the changes in our planet’s climate.

So how does a developed nation like Australia aim to transition its economy and society? How can it effectively mitigate its contribution to CO2 emissions and adapt to the impacts?

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison received scathing criticism over his actions in responding to this disaster. On January 4th, after much damage had already been done, he finally agreed to a request made 18 months earlier for A$20 million to lease 4 extra firefighting water-bomber aeroplanes. Morrison also called out the defence force reserves, and approved a relief package for recovery for citizens affected by the Australian bushfires.

As former IPCC author and US climatologist Professor Michael Mann said, in Sydney, Australia during the crisis, not only was this unprecedented but to paraphrase: “you ain’t seen nothin’ yet”. Mann also reminded Morrison and his laissez-faire government that it needs to take its national and international responsibilities seriously.

“This is not the new normal, this is worse … This is what happens with 1°C warming, imagine what it will be like with 3°C.”

Prof Michael Mann on Australian TV, January 2020

In the face of the largest environmental disaster ever to befall the country, some Australians are now calling for a A$1/tonne carbon tax or levy on fossil fuel production. To aim for complete decarbonisation of the economy the IMF recommends far higher carbon taxes.

Even though this $1/tonne taxation on carbon emissions may generate considerable income for the government, it is designed to have an inconsequential effect on the mining industry – it’s proposed as a means to raise funds for compensation and adaptation, not mitigation.

Even so, there is little chance that the Morrison government would implement a $1/tonne tax. They have also declared that they consider their current policies sufficient to meet international emissions obligations. The usual adage was trotted out about how small Australia’s contribution is on a global scale. The government prefers a technical solution to any 2050 target.

So close and yet so far

What is astonishing is that a few months before this disaster unfolded, in May 2019 Australia came tantalisingly close to voting in a Labor government that pledged substantial and meaningful climate action.

Labor was ahead in the polls in the years leading up to the 2019 general election, which many observers saw as unlosable for the party.

Believing the electorate was primed for climate action, Bill Shorten, the Labor leader, took the decision to make action on global warming the centrepiece to his campaign. Australia had already been traumatised by major bushfires and coral bleaching events and had been observing global warming-related impacts on the increase worldwide.

“It is not the Australian way to avoid and duck the hard fights. We will take this emergency seriously, and we will not just leave it to other countries or to the next generation. We are up for real action on climate change now if we get elected on Saturday.”

Bill Shorten, campaign speech

Shorten’s decision to focus on climate action was well founded. This strategy aligned with the annual Lowy Institute poll which showed over 60% of Australians agreeing that ‘’Global warming is a serious and pressing problem’’ and that steps should be taken urgently, even if it involves significant cost. To compare, in 2016 only 9% of people identified climate change as the most important issue, while in 2019, this had risen to 29%. With this data to back him up, it made sense that Shorten saw this election as an opportunity for meaningful action on climate change.

For the first time anywhere in the world, the issue of climate change was to be the decisive topic in an election. Australia was on the brink of being the first developed nation to vote for climate action over business-as-usual.

So did Australia, with one of the highest per capita carbon footprints in the developed world at 16.77 tonnes of CO2 emitted annually, accept Shorten’s call to action? The “unlosable election” was, in fact, losable. Despite correctly identifying the upward trend in support for climate action, the people of Australia were still not ready for Shorten’s bold strategy of disrupting Australia’s economy for the sake of the planet and future generations. Scott Morrison, the leader of The Liberal National Coalition, proved all the polls wrong and was able to steal victory, to the glee of climate sceptics and denialists across the globe.

It is important to note key shortcomings in the Labour campaign that contributed to their loss. The most pertinent reason, according to the party’s official post campaign review, was the lack of direction in the campaign strategy. The review discovered that new spending polices were often established on the spot. The effect this had was that the labour campaign ‘’lacked focus, wandering from topic to topic without a clear purpose.’’

For a climate-focused campaign, one which demands careful persuasion to convince the constituents to accept the necessary changes, this cocktail of disorganisation loaded the dice against Shorten. For example, spending announcements of over A$100bn exacerbated already unpopular tax policies, exposing Labor to coalition attack. The review further found that low-income workers swung against Labor, in part thanks to the ambiguous language about controversial topics such as the Adani coal mine.

If concerned voters are going to commit to radical measures like Shorten’s climate policies, they need the politicians to offer clarity, security, conviction and direction. Shorten’s Labor party claimed to offer substantive climate action, but simultaneously fostered a perception of uncertainty and lack of direction.

This was the key shortcoming in Labor’s climate action campaign. For the constituents, the common and pervasive assumption about climate action was that it would lead to significant impacts on people’s material wealth. The Labor party did little, if anything, to address this worry. The message lacked clarity as voters were presented with accounts of relatively extreme policy measures, all likely to deliver a significant blow to the economic prosperity of Australia.

Common tools for climate action

The presumption of massive costs for the voters is understandable when most climate-related policy tools are seriously socially regressive. As a share of income, spending on high carbon products and services is much greater for poorer people, impacting them disproportionately to the rest of the population. Despite this, carbon taxation is now widely used across the globe and regarded as the most important tool to drive down emissions. About 47 regional and national jurisdictions worldwide have implemented a carbon tax scheme.

In some cases, it has proven successful. British Columbia for example, is lauded for their version of carbon tax. They currently have a levy of CAN$30/tonne on selected fuels. After implementation, gasoline use shrank seven times as much as would be expected from an equivalent rise in its market price.

But what about the disproportionate effect this has on the less affluent? The CAN$5 billion revenue from the tax is redistributed in the form of business tax cuts ($3billion), personal tax breaks ($1billion) and just under $1billion in low income tax cuts. To overcome the regressive nature of the tax, British Columbia pays an annual dividend, known as the “Climate Action Tax Credit”, of $115.50 for each parent and $34.50 per child annually. Overall, the carbon emissions of British Columbia have been significantly reduced and the populace accepts the tax and dividend approach.

Clearly, if managed correctly carbon pricing can work. However, success is the exception. Failed and ineffective schemes out-number these successes substantially. If we look to the European Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), the largest in the world, we see that it has been a seriously rocky road to reach an estimated emissions reduction of 40-80 MtCO2/year, equal to a relatively paltry 2-4% of total capped emissions.

Since its inception in 2005, the EU ETS emissions price has been very volatile, seeing several collapses of 30% or more. These frequent swings in energy prices made it harder for businesses to plan, further compounding the cost of the scheme and reducing its impact.

Huge windfall profits were allowed as a surplus of €4.1billion in allowances were captured by ten companies, four times the entire EU environment budget over the same period. Known as the carbon fat cats from the iron, steel and cement industries, their emission allowances amounted to the annual emissions of Austria (87 million tonnes CO2), Denmark (64M tCO2), Portugal (78M tCO2) and Latvia (12M tCO2) combined.

Any scheme tasked at reducing CO2 emissions must perform better than this. So yes, the EU ETS has been successful in bringing down overall carbon emissions, but whether it really achieved anything close to its targets for 2020 is debatable (see the Ember/Sandbag report). Its effectiveness is heavily dependent on the correct allocation of allowances by decision makers and the scheme has been mired in controversial errors, over-complications, industry lobbying and non-climate-related political agendas.

With the perception in Australia that the sharpest tools in the policy toolbox were somewhat blunt, it was no surprise that Shorten failed to assuage voters’ concerns on costs.

To show the inadequacy of carbon tax, a 2019 review of carbon pricing policies by the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy made a recommendation on the costs and benefits of carbon pricing. It concluded that the best solution is not aim for market impact by reducing demand, but rather to have only a moderate carbon price with the main purpose of generating revenues for subsidies and investment in carbon reduction measures, such as renewable energy, CCS and natural carbon storage.

The goal of internalising all the social and environmental externalities associated with the emissions and to drive down demand was regarded as simply too ambitious.

Now in 2020, climate targets for 2050 probably seem popular, achievable and defensible to decision makers, but the route to zero emissions can only be through a series of substantial and radical steps – not a leisurely pace followed by a gargantuan effort in the 2040’s.

Yet that is the path of business-as-usual, where “usual” is defined by the imperative of economic growth, and not by the realities of global warming. It becomes alarmingly clear that avoiding Climate Hell cannot be done with carbon taxes. Taxes have a role to play, but if they take the starring role in climate policy, the result is most likely to be a series of missed targets.

The failure to seek out new policy mechanisms to drive decarbonisation was identified in a recent UNEP report which found that without more meaningful action the Paris Agreement 1.5°C target will slip out of reach.

So, considering the inherent issues with the established policies, how could Australia’s Shorten or any other politician successfully fight an election on the climate ticket? What is politically realistic? How can a party craft a meaningful environmental strategy which reduces emissions and is socially just, but doesn’t alienate middle class voters and business?

The need for a new tool

A suitable political strategy has so far remained elusive. What is needed is a new framework with a clear, coherent agenda that appeals to the majority. This includes both the rich and the poor, ethnic minorities, fossil fuel companies and renewable energy providers, the political right and the left, and internationally, developed and developing nations.

Current action is stifled by the rifts between these various groups as they debate how to face the crisis with the current portfolio of weak policy tools.

Too much time and energy is dedicated to brokering compromise between factions, all vying to forward their own agendas for the future. And as we have seen with current negotiations on the international scale at COP25 in Madrid, the Paris Agreement Article 6 proved too big a stumbling block.

This small detail stipulates the time-frame of carbon emission targets, with developed nations wanting 10 years to reduce their emissions in line with the Paris agreement while developing nations want 5 years. Why not 7 1/2 years? Obviously negotiations should lead to compromise, but a hard truth needs to be accepted here. If the world’s leaders cannot even agree on relatively trivial caveats to climate action, how then is society going overhaul our economic and social systems within the time-frame available?

Bearing that in mind and knowing where business-as-usual is leading, it’s obvious that the required “radical” and “drastic” action, which fits in with the wants and desires of an electorate, can only be one thing. Peering into our toolbox, we realise there is still another tool which has yet to be tried. Decried over a decade ago as too “radical” and subsequently forgotten, it is carbon rationing.

Total Carbon Rationing – both citizens and business

Carbon rationing is the most progressive economic mechanism for driving down a country’s CO2 emissions. Unlike taxation, which impacts the poorest the most, it puts pressure on the most flagrant carbon users to reduce their emissions. Importantly for business, its agency works within market mechanisms. In this way, its usefulness and potential are not limited by biases which afflict carbon taxes.

Critically, it is the fairest of carbon policies because the rations are allocated to citizens on a per capita basis. It is also transparent and simple for governments wishing to adjust individual allocations to citizens with special considerations. Whether that is National Health Service nurses or Prince Harry is up to the politicians leading on the implementation.

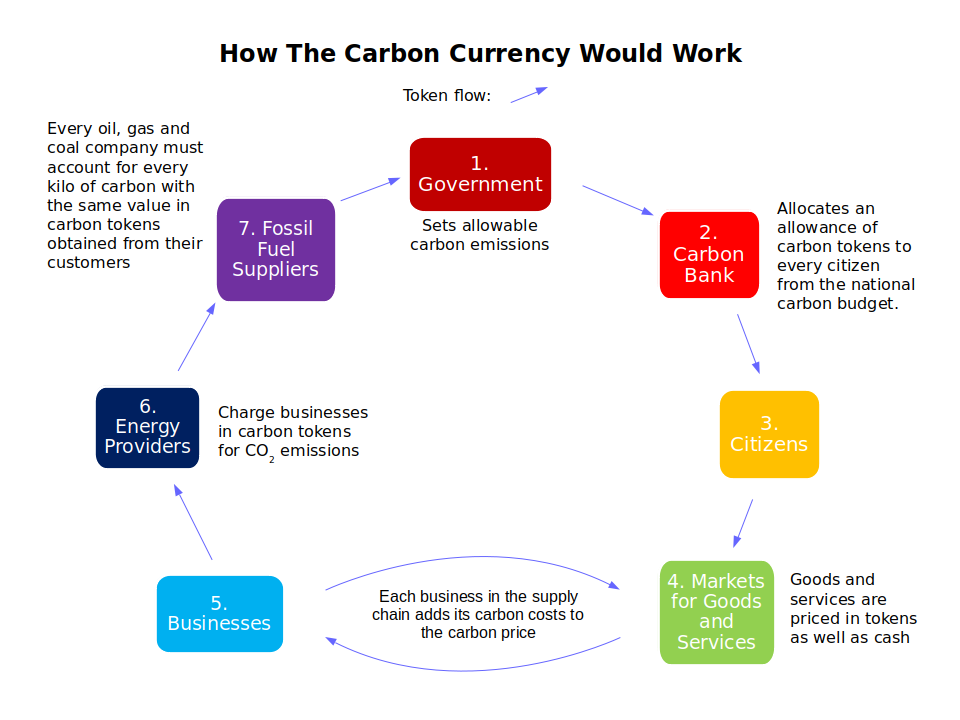

The Total Carbon Rationing policy proposal outlines how all goods and services bought or sold within the economy would be subject to the payment of rations – right through the supply chain from citizen-consumer to oil company producer. In essence, it will be a new currency in the form of carbon rations, distributed on a regular per capita basis to all citizens. All citizens would have the right and ability to spend this however they please in tandem with their usual money.

For example, whoever wants to purchase a new car, must pay the car dealer in money and rations. The car dealer pays the car manufacturer with rations as well. The manufacturer pays several suppliers, also with rations, including a steelworks, an energy provider, a battery manufacturer and so on. The steelworks obtains its rations from its customers, like the car manufacturer. It knows how many rations to charge, because it has to pay rations for the energy it uses in its furnaces – whether to a fossil fuel supplier or, in much smaller quantities, to a renewable energy source. The total amount of rations in the economy directly limits the amount of fossil fuels allowed to be pumped out of the ground.

The start-up costs of implementing carbon rationing are large, but it is already established that the action needed has to be radical and drastic. Similar actions at a national level have been taken before – the decimalisation of the British currency, metrication, the creation of the Euro, and of course, war-time rationing.

The overall effect is that companies will get a direct, immediate competitive edge from improving their carbon efficiencies, without any complexities or shenanigans from a carbon taxation system or any red tape from government regulation. It will create a shift simultaneously across all industries and sectors to a new state in which driving down carbon emissions is as vital as driving down monetary costs of production. This ubiquitous effect is what carbon taxation and carbon pricing have failed to achieve.

This circular flow of carbon rations from citizens to fuel producer is driven by the energy companies. The carbon rations they collect from customers must match the amount of carbon they pump out. Importantly, a market for carbon will be created for individuals and businesses needing to buy or sell rations. This puts pressure on big carbon users as they are forced to buy more carbon rations at a fair price on the market set by the more environmentally aware or thrifty who have surplus to sell.

Finally, a centralised bank would be established to monitor and audit the energy producers. The bank would have the power to progressively reduce the amount of carbon rations in the economy to drive down emissions in accordance with the Paris Agreement of keeping warming below 1.5°C. This supply control is what gives carbon rationing so much potential for keeping within our carbon budgets. With the current state of the climate and the economy in 2020, a sharp decline in emissions is needed and carbon supply controls are the key tool for balancing emissions reduction against economic damage.

To start, the total national carbon ration quantity could match or significantly exceed the current levels of emissions, to allow citizens to adapt to the introduction and prepare themselves for future restrictions. If implemented now, CO2 emission reductions could be achieved at the ideal optimal rate, at a rate which people could realistically handle, at a rate that allowed business to adapt their total supply chains and not fail, and at a rate that could hold total global warming as far under 2°C as possible.

For more information, use read the explainer, check the Q&A section or read the full Total Carbon Rationing (TCR) proposal.

Australia as the model country

With this new tool to hand, in a developed country populated by most constituents believing that climate breakdown is a significant issue, Bill Shorten’s election campaign might really have been unlosable. If he had embodied Total Carbon Rationing as the backbone to his campaign, he could have established a clear direction and purpose.

This is far from the reality of Australia in 2020. It is fair to say that carbon rationing would create an Australia unimaginable under Prime Minister Scott Morrison. As mentioned earlier, Morrison’s response to climate change warnings and his disingenuous climate policies garnered widespread criticism. It is obvious that the fossil fuel industries hold sway over Morrison’s agenda.

Australia is currently ranked as the worst of 57 countries on climate change policy. In June of 2019 any hope of Morrison’s cabinet overcoming its fossil fuel addiction was dashed as the former Minerals Council of Australia CEO Brendan Pearson was appointed as one of Morrison’s senior advisor. Clearly not even half-measure carbon pricing policies would get past Morrison.

So how would a new agenda such as TCR survive the influence of the big fossil fuel industries in Australia? They will likely be a substantial roadblock for rationing. Mining for export has long been the cornerstone of Australia’s economy, with the number of companies totaling over 700. And it is the most dirty of all, fossil fuels, that hold the highest value of exports at US$87.7 billion in 2019, representing 34.6% of Australia’s total exports.

To play Devil’s Advocate, national rationing in Australia would allow a politically adept avoidance of confrontation with the Adani coal mine and the extraction industry – by considering it as an exported emissions problem to tackle later, which would only fall under an Australian carbon rationing system once India and China (the Adani customers) joined Australia in a carbon rationing trading block.

Initially, if Australia imposed carbon rationing through a new carbon authority, it could set up the rationing comprehensively domestically and on imports at the border. This would mean, to begin with, TCR would only affect domestic industries. The policy could effectively drive down domestic emissions without disrupting exports. On the other hand, with the carbon ration borders, it would discourage emissions imports.

Essentially national rationing would separate the exported emissions issue from the domestic emissions issue. This doesn’t fit the 2020’s popular narrative of packaging all policies into one manifesto such as the Green New Deals, but removing the controversial Adani coal mine from the debate might just be enough to pull in the required votes.

The reality is that a carbon tax which will hit Australia’s economy will struggle to pass, but TCR can be promoted as a policy of choice for these industries. It would allow a huge part of the Australian economy to continue over the short term.

Instead of creating concern over some industries’ future and incurring massive costs, it just puts the writing on the wall through the creation of a straight and narrow path, a period of adaptation, with continual, regular decreases in demand for carbon.

Instead of threatening the removal or over-pricing of a range of popular products, services and activities, TCR only enforces a reduction across the board, where consumer choice is still guaranteed as long as the consumer is not a flagrant carbon abuser.

Instead of taking on far more than a “fair share” nationally, Australia could adopt a policy which guarantees Australian decarbonisation now, and could fit into international negotiations transparently and fairly, and could create some huge synergies in international trade if other countries adopt the same policy.

Instead of a campaign which divides and polarises voters, carbon rationing could be put forward as a fair and effective strategy with clear costs but a real purpose, justified by the country’s vulnerability to wildfire, coral reef bleaching, flooding, drought and refugee crises.

60% of Australians want climate action. The carbon emissions of every purchase of goods or services are abundantly clear under carbon rationing. Combined with the freedom of choice in trading off lifestyle against carbon footprint, TCR would allow voters a means to turn their attitude into meaningful behaviour.

In short, TCR could have saved Shorten’s election. He could have been the first person to effectively communicate to voters on climate, to demonstrate that climate action need not be divisive, but unifying. That it doesn’t have to mean sacrificing to their complete way of life.

Implementing TCR, putting rationing like this in place, begs the question whether society really wants this, and can really do this. It is certainly a radical and drastic approach only ever seen before in war-time. But the evidence shows two things: that all the other policy tools at our disposal are significantly inferior on many levels to the point of being useless and even dangerous; and that the global economy is now at a point where there is no more room for mistakes in addressing the climate crisis.